By Haukur F

14th October 2021

Meet the Brass Teacher who Helped a Whole New Family of Instruments Go Suzuki

It is the hottest day in June since 1947 in Sweden and Ann-Marie Sundberg has just come back to her home in southern Stockholm after her morning walk in the nearby park. Although Ann-Marie’s day has started early, on the other side of the Atlantic, her brass teacher trainees taking Unit 1 at the Intermountain Suzuki String Institute are still fast asleep.

Zoom, distance learning, camera angles, lighting, “original sound”—yes, Ann-Marie has had to master a whole new vocabulary and technical know-how in the past eighteen months like the rest of us. But who would have thought Ann-Marie could train Suzuki brass teachers in the United States from her living room in Stockholm before the pandemic?

“It has been a journey” Ann-Marie says in an in-person interview. “Challenging but very interesting. And, with some surprises! Perhaps the most notable one is that I can do this and actually enjoy the possibilities this new technology offers.”

Why train Suzuki brass teachers from your living room?

“I have known about the Suzuki Method for most of my career,” Ann-Marie says.

Ann-Marie is a former trumpet player in the Norrköping Symphony Orchestra, brass pedagogy lecturer at the Royal Stockholm College of Music, a published author of several trumpet schools, and successful brass teacher in three countries.

“Many of my violin teacher colleagues were Suzuki teachers and I was always envious of their results and of the work environment that they created with their tools from their Suzuki teacher training,” Ann-Marie says. “I wanted this too for my trumpet teaching! However, when I asked, I found out that there was no Suzuki approach for the trumpet or other brass instruments.”

That did not stop Ann-Marie. Having played the violin as a second instrument in her youth, she dusted off her old violin and enrolled in one of the first Suzuki teachers’ courses given by John Kendall on one of his many visits to Sweden in the early 1980s.

“It was an enriching experience, although, my violin playing did not improve that much! The philosophy, the use and structure of the repertoire, and the emphasis on tone as well as the use of both individual and group lessons were elements which I, as a brass player and teacher, could strongly relate to.”

A number of years passed. In Norway, brass players had also been inspired by the other Suzuki instruments. The Association of Norwegian Brass and Wind Bands funded an exploratory project (called Rett på musikken – Right on the Music) to find out whether it was possible to develop something similar for brass instruments. Anne-Berit Halvorsen, a Suzuki violin teacher in Oslo and then Chair of the Norwegian Suzuki Association and Board Member of the European Suzuki Association, was instrumental in getting this started and involving trumpet and trombone teachers in this project.

During a shared airport taxi ride with the writer of this article (who at the time was the Chair of the ESA) to the Annual General Meeting of the European Suzuki Association, Anne-Berit shared her thoughts on the project and emphasized the necessity to steer it towards a more formal “Suzuki” direction by the ESA. A food for thought for the Chair.

How did you get involved with the development of Suzuki trumpet and later all the brass instruments?

“It was all your fault! You were one of my bosses at the time at the Nacka Music School outside Stockholm. One day we were talking in your office and the subject of Suzuki came up. One thing led to another and the end result was that you asked me to be the project manager of this ESA project, which was to develop the Suzuki Method for trumpet,” Ann-Marie says.

A number of busy years followed. Ann-Marie was also working as a brass pedagogy lecturer at the Royal Stockholm College of Music at the time and the music college gave her a grant to do research and to start a test group of young children.

Ann-Marie travelled to several countries to observe Suzuki teaching on various instruments and disciplines. At home, she followed a Suzuki teacher training course on the cello while discussing her work with Suzuki teachers and teacher trainers in Europe. “I studied the Suzuki repertoire of a number of instruments, in order to analyse the necessary technical progression needed for the first Suzuki trumpet book. And I looked critically at my own instrument, the trumpet, to see how the instrument and the early stages of learning could be adjusted to a young child of four years old,” Ann-Marie says. “All of this was an interesting and challenging journey, which broadened my horizon as to the possibilities of the trumpet.”

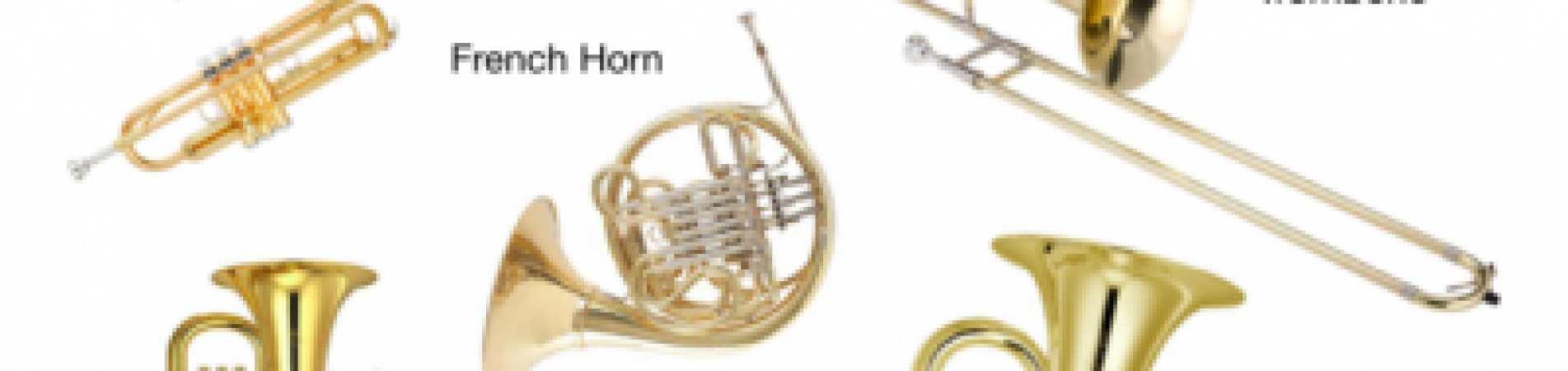

After a few years of development work, the International Suzuki Association accepted the trumpet as a Suzuki instrument in 2011. This decision was later augmented to include all brass instruments.

“That was a great point,” Ann-Marie says. “It was, however, the beginning of a process that has continued and is continuing to this day,” she adds. Ann-Marie became a Suzuki teacher trainer in 2013. She started training trumpet teachers in Sweden, and later in Canada, the United States, Mexico, and Brazil. Meanwhile, the first Suzuki Trumpet book was tested and commented on by a large group of trumpet teachers. “I would like to think that although I provided the initial research and ‘skeleton’ for the books, they are a collaborative effort of all the wonderful teachers who have taken time to play, teach and comment on the books since the beginning,” Ann-Marie says.

What has it been like to work on Suzuki Trumpet Book 1?

“A long and arduous but very rewarding process,” Ann-Marie says.

Publishing Suzuki ground material is a painstakingly detailed project. The Suzuki books, containing the ground material, are published by Alfred and Ann-Marie has been working tightly with them as well as with the ISA’s International Brass Committee, of which Ann-Marie is the Chair.

“I have prior experience in working with a publisher in Sweden when my books on trumpet playing were published, so I knew what to expect,” Ann-Marie says. “I am very happy to see that Suzuki Trumpet Book 1 is now on the market, together with the excellent recording of Caleb Hudson, assistant professor of Trumpet at University of North Texas and a member of the Canadian Brass,” Ann-Marie adds. She says she is “indebted to my colleagues on the ISA Brass Committee”: Natalie DeJong, trumpet faculty at Mount Royal University Conservatory in Calgary, Canada, Astrid Nøkleby, trombone teacher from Oslo, Norway (who also participated in the original Right on the Music project) and Brenda Luchsinger, assistant professor of music (French horn) at Alabama State University, Montgomery, Alabama. “I would like to thank all of them for their great work and dedication.”

Are there any particular challenges entailed in adopting the method for brass instruments other than the trumpet?

“The basics are the same,” Ann-Marie says. “Fairly soon after the beginning stages, there are, however, some variations in technical development that some of the other brass instruments need to address. Here it can be an issue of keys and in some cases, additional repertoire is needed,” Ann-Marie adds. “Most of the repertoire of the first three books can, however, be played by all of the instruments.”

What does the future of Suzuki brass look like?

“We now are 91 Suzuki brass teachers in 21 countries, the latest being Argentina and Thailand, and we are a strong dedicated international community,” Ann-Marie says. “I will not be around forever to spread the word, but I will make the utmost effort to do so in order to see the future of Suzuki brass secured. I want to reiterate, however, that I see Suzuki brass as a collective project belonging not only to all Suzuki brass teachers but to the Suzuki community as a whole.” “It is the responsibility of the entire Suzuki brass community to make sure that the quality of tone and the quality of teaching continues,” Ann-Marie says. “It is also our collective responsibility that Suzuki brass is available for children and that their teachers have the opportunity to train as Suzuki brass teachers, thereby gaining the teaching tools necessary to pass the joy of brass playing to their students.”

“After all, Dr. Suzuki said that ‘Tone has the Living Soul.’ I know I am biased, but what is more beautiful than the full rich tone of a brass instrument!? I want children all over the world to have the possibility of experiencing this and hope that the Suzuki community will continue to make that happen.”

It is now late afternoon for Ann-Marie in Stockholm. The lights are on, the laptop is on, the two cameras are positioned. Zoom is updated (very important) and opened to the right meeting.

“Good morning, everyone!” Ann-Marie says to the smiling faces in all of the small Zoom rectangles. “I hope you have all had a good night’s sleep. Now we continue where we ended yesterday.”

And, through the wonders of technology, Unit 1 Suzuki Brass teacher training course continues. Next week it will be Unit 2 at Mount Royal University Conservatory, in Calgary, Canada.

This article was first published in the SAA Journal in August 2021

About the author:

Haukur F. Hannesson holds a PhD and an MA in Arts Policy and Management from the City University in London, UK. He also holds an AGSM in Cello Performance and Teaching from the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London. Haukur was one of the first Suzuki cello teachers in Europe and holds the Diploma of the ESA (Level 5). He is a recognized Suzuki teacher trainer by the ESA, SAA and ARSA. At the beginning of his professional life, Haukur was a cellist in the Iceland Symphony Orchestra and in 1988 founded the Reykjavik Suzuki School of Music, in Iceland. After moving to Sweden in 1994, Haukur was the CEO of two professional Swedish orchestras as well as deputy director for the Nacka Music School, outside Stockholm. In recent years he has been teaching cello and conducting student orchestras in the city of Västerås, Sweden, where he now lives with his husband of 27 years. Haukur has published a number of research articles on the subject of arts policy and music pedagogy in scholarly journals and was the Chair and Deputy-Chair of the ESA for a decade and a half. He was on the Board of Directors of the ISA for 16 years, serving as Chair, Vice-Chair, Secretary and Treasurer.